The surprisingly unromantic origins of Valentine’s Day

Valentine's Day hasn't always been flowers, chocolate and saccharine romance

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

Loved by some, loathed by others, Valentine’s Day is widely regarded as the ultimate day of cheesy, unapologetic romance.

While some may be vaguely aware that the occasion takes its name from a priest called Saint Valentine, they may not be acquainted with the full history of Valentine’s Day, which is decidely less romantic than one may expect.

Valentine of Terni was a Third-Century-priest who ministered to Christians in ancient Rome. Various accounts exist detailing the events that led to him becoming a martyr and subsequently being named a saint by the Catholic Church.

One of the most widely-believed accounts suggests that Valentine defied Emperor Claudius II of Rome. The Emperor had outlawed young men getting married, as he thought them to be of more use on the battlefield than at home.

Some accounts detail Valentine’s stark defiance of this law, seeing him marry young couples in clandestine ceremonies. This was regarded as a serious offence in the eyes of the Emperor, and the priest was beheaded on 14 February as a consequence.

Despite the emperor’s wrath, the Catholic Church commended Valentine for uniting couples who observed the Christian faith. Thus, Valentine was formally recognised by the church as a saint after his death. Saint Valentine has since become associated with courtly love and the romantic traditions of Valentine’s Day.

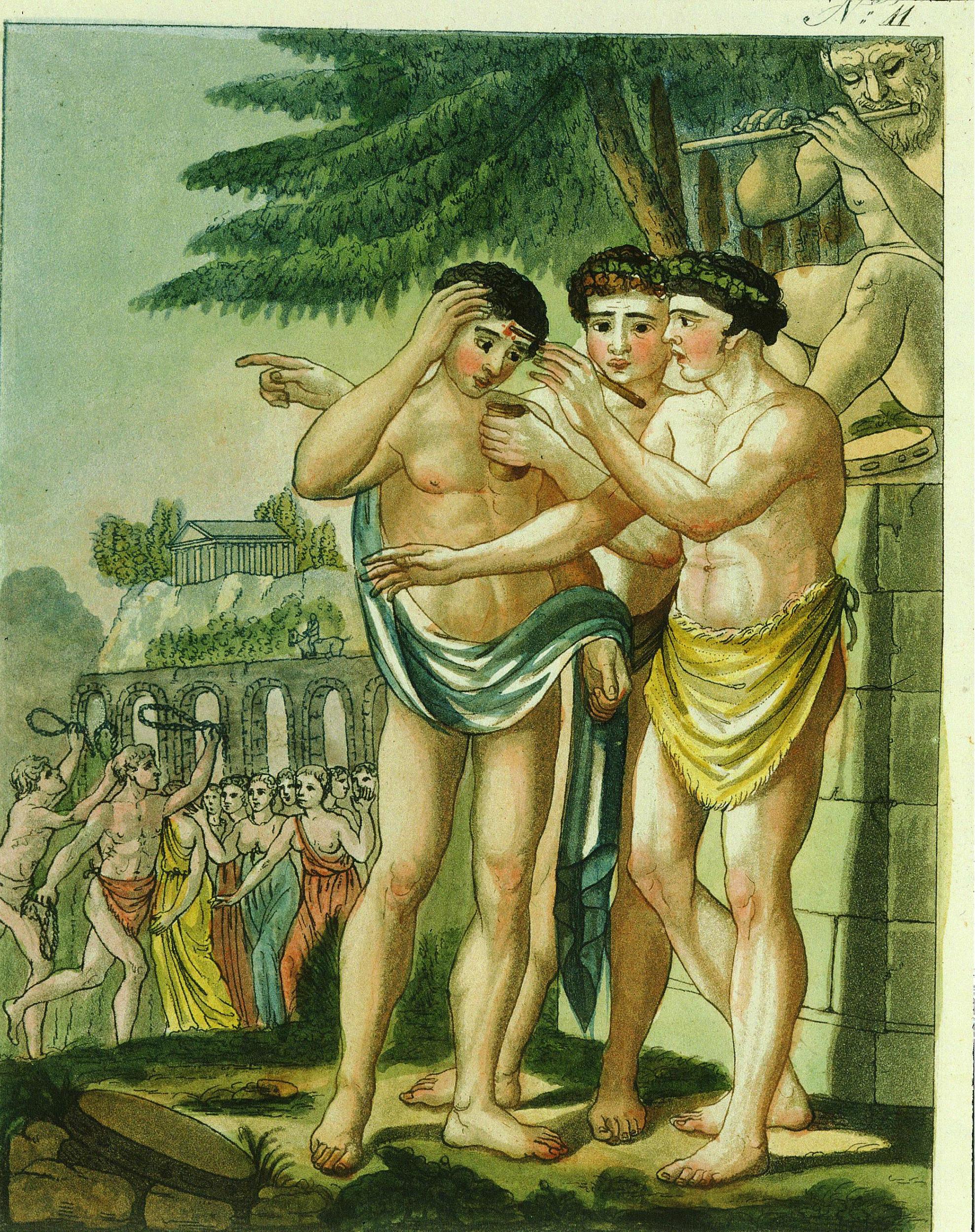

Along with this account, some believe that the history of Valentine’s Day may also be rooted in a pre-ancient Roman festival called Lupercalia. The festival, which was celebrated every year by Romans on 15 February, celebrated fertility. Those who took part worked to purify the city of evil spirits in order to maximise fertility and bring prosperity to their villages.

The pagan festival was also known as “dies februatus”, meaning “day of purification”, which is how the month of February acquired its name.

Part of the proceedings saw the priests of the god Lupercus – the Luperci – sacrifice goats and a dog and then daub their foreheads with the animals’ blood.

These men would then run around the Palatine Hill naked, striking any women who came near them with the hides of the animals that they’d sacrificed. The priests believed that hitting women with the animal hides would ensure that they’d remain fertile.

While the concept of Lupercalia may differ greatly from our modern understanding of Valentine’s Day, the two observances are closely connected.

The celebrations of Lupercalia came to an end around the 5th Century, following objections made about the festival by Pope Gelasius I.

The pope condemned the practises of the pagan festival, describing those who participated in it as “vile and common, abject and of the lowest order”.

The holiday of St. Valentine’s Day on 14 February was officially declared by the pope in 496 AD, leading some to believe that he had effectively replaced Lupercalia with the holiday honouring Saint Valentine.

The first evidence of Valentine’s Day having romantic connotations came in the 14th Century, through the poetry of Geoffrey Chaucer. “For this was on St. Valentine’s Day, when every bird cometh there to choose his mate,” the English poet wrote to honour the engagement of King Richard II and Anne of Bohemia.

William Shakespeare also referenced Valentine’s Day in his work, having Ophelia speak of the day in his 17th Century play Hamlet.

Valentine’s Day as we know it today started to take form in the 19th Century and early 20th Century, thanks in part to the boom of the industrial revolution.

In 1913, Hallmark Cards in Kansas City, Missouri, began mass-producing Valentine’s Day cards, sparking the beginning of the commercial holiday the 14 February has become.

A decade later, chocolatier Russell Stover had the innovative idea of selling chocolates in heart-shaped boxes, encased in satin and black lace.

In 2018, money saving website Finder reported that 22 million Brits were preparing to spend money on their significant others on Valentine’s Day.

The average spend for an individual taking part in the love-filled celebrations was £28.45, while 16 per cent of the population stated that they planned on celebrating the day without spending a penny.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments