Sheep-shearing school promises greener pastures to children of Birkenhead estate

Woodchurch High School pupils get stuck in looking after sheep, alpacas, goats and pigs, giving them a real taste of agricultural life

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

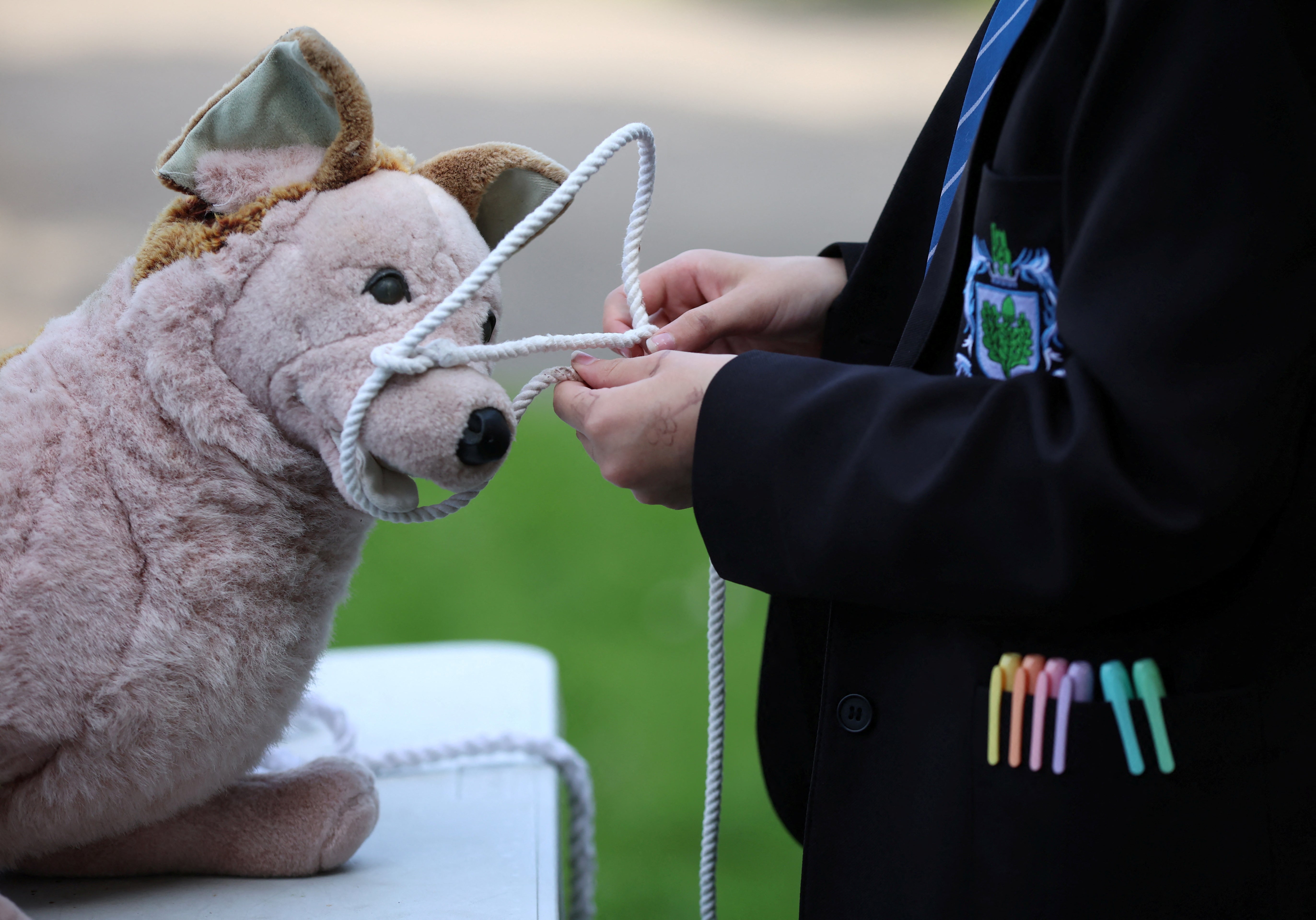

The rural life of rearing rare-breed sheep and caring for alpacas is a world away for many urban teenagers. Yet a British school near Liverpool has opened up a wealth of jobs in agriculture and the benefits of nature for its pupils, by establishing its own farm.

The Woodchurch High School farm opened 13 years ago, becoming a haven that nurtures the mental health and confidence of its students.

Based in the town of Birkenhead, which faces Liverpool across the River Mersey, the school counts dairy farmers and veterinarians among its former students, and some of them say the school’s farm is the reason they found their calling in life.

Woodchurch itself ranks in the top 10 per cent of local areas in England for income deprivation. Last month local authorities announced that the nearby leisure centre would be demolished.

And with UK social mobility at its lowest ebb in more than 50 years, restricting people from moving to a higher income level, the capacity of the farm to expose its students to people and professions far removed from the school’s urban trappings is more important than ever.

“It is really important that [young people] have an opportunity to achieve, to thrive, to actually show skills,” headteacher Rebekah Phillips says, adding that the project has also helped to support social and emotional development.

Each year the students compete in the prestigious Royal Cheshire and Westmorland county shows, displaying skills gained by looking after their sheep, alpacas, goats, pigs and chickens. Many have won both prizes and acclaim from farming experts.

“The farming and agricultural communities have opened their arms to us,” Linda Hackett, the farm manager, says.

Year 10 pupil Ella-Rose Mitchinson, 14, was awarded Student of the Year 2023 by the School Farms Network – a collection of 140 schools, many in rural communities.

For her, the farm represents a safe space, away from the world of social media and the rigours of teenage life.

“It lets me breathe,” she says, adding that she dreams of becoming a veterinary nurse.

Year 8 pupil Corey Gibson, 13, agrees.

“It provides a happy place where you can be yourself. Animals won’t judge.”

Former pupil Sophie Tedesco, 27, now works as a dairy farmer in Shropshire, having first tasted farm life at the school before she left it in 2013.

“It opened my eyes to the agricultural world,” she says. “It was just completely different to what we were used to, and I just loved it.”

Increasingly the school is recognised as a centre for conservation – following a stroke of luck, when it was gifted North Ronaldsay sheep at the farm’s opening in 2010.

Originally from Orkney, the sheep are listed by the Rare Breeds Survival Trust as one of four “priority” breeds – the charity’s highest grade of concern.

“Our little school, over 13 years in our one-and-a-half acres, has bred over 60 sheep. We’ve had lambs every year. Our sheep count towards the national census for the Rare Breeds Survival Trust,” farm manager Hackett says.

Headteacher Phillips says other schools have shown interest in the farm, but she laments the fact that it is never taken into consideration in the country’s academic review system, despite the broader community impact.

“We have never had one bit of vandalism, ever, in 13 years,” Phillips says. “I think the worst incident we ever had was the uproar when a child fed a sheep a crisp.”

Reuters

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments