Anna May Wong and the mystery of Hollywood’s first Chinese-American star: ‘They wanted to tear her apart!’

A new book dives into the life and death of the first Asian superstar of American film, from her struggles for industry acceptance to her rumoured fling with Marlene Dietrich. Charlotte O’Sullivan meets its author

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

Anna May Wong was Hollywood’s first Chinese-American star, a gifted actor who refused to allow racism and sexism to stymie her career. She was one of the silent era’s most popular celebrities, but was often cast in demeaning roles: women who were minxy and exotic, or doomed, sly and treacherous. Wong was gorgeous, willowy and insouciant (in terms of body type and attitude, Wong’s modern-day equivalent would be Zendaya). But Hollywood’s studio heads were “blinded by their own prejudice”, says Katie Gee Salisbury, the author of a new biography of the star. The book details how Wong set off for Berlin, and later London, in search of more nuanced roles.

The gamble paid off. The European films Wong made in the late Twenties – Song, Pavement Butterfly and Piccadilly – are politically provocative and beautifully lit, all of them place her centre stage. In close-up shots, her frequently anguished eyes resemble melting scoops of ice cream. Hollywood, by now making talkies, got the message. Upon her return to the US, she was offered (if only grudgingly) better parts. In the 1932 classic Shanghai Express, Wong is a sardonic and fearless sex worker who enjoys the company of a libidinous gal pal, played by Marlene Dietrich. The pair’s chemistry is the stuff of legend.

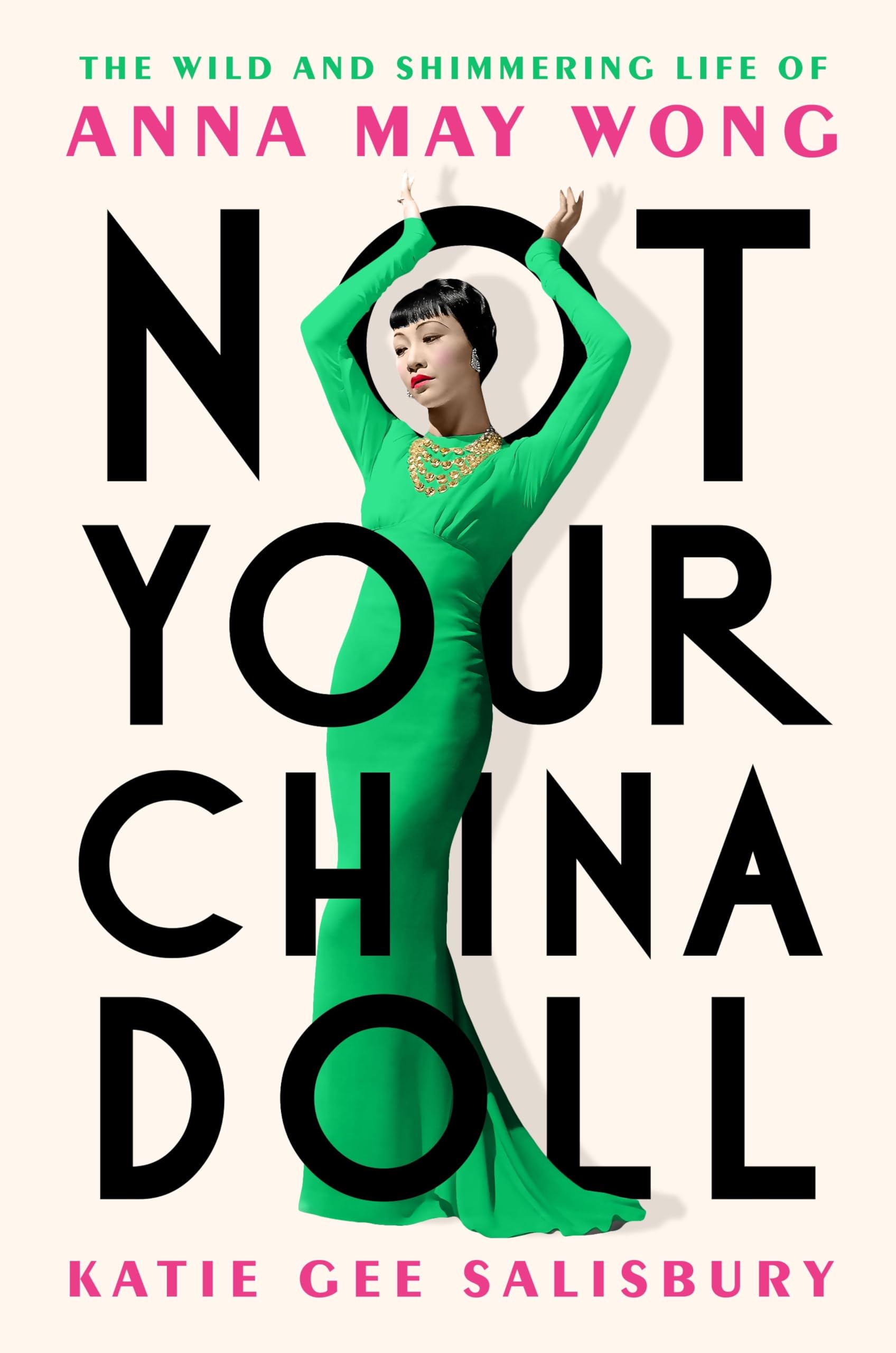

But a supposed affair between them, Salisbury says, is just one of the narratives surrounding Wong that she wanted her biography – titled Not Your China Doll – to challenge. Video-calling from her apartment in Brooklyn, New York, Salisbury tells me that the many biographies of the star already in existence fail to capture the real Wong. For starters, they were all written by men, and they all push a theory “that, to me, sounds more like male fantasy than the truth”, Salisbury says.

It gives her no joy to put the record, ahem, straight when it comes to Wong’s sexuality. “I think it’s amazing how she’s been embraced by the queer community and I hate to be the one who says, ‘Er, I don’t think that she was!’,” she laughs. “But there just isn’t anything to corroborate it.”

Which is why Salisbury “disagrees” with Graham Russell Hodges and Yunte Huang, the authors of two previous Wong biographies. “They bring up rumours about Wong and Marlene Dietrich having an affair,” she says. “They ask ‘Did Anna May Wong have affairs with other women?’ As a woman, I’m a bit suspicious of people projecting these ideas of affairs, based on one photo of Wong, Dietrich and Leni Riefenstahl. Based on that photo everyone decides, ‘Ooh, maybe they’re all sleeping together!’”

Salisbury describes Hodges’ 2004 book (Anna May Wong: From Laundryman’s Daughter to Hollywood Legend) as “very dry” and points out that Hodges is “Caucasian American – he didn’t grow up in Asian culture, so he’s looking at it as an outsider”. She adds that while Huang – whose book, Daughter of the Dragon, was published nine months ago – “is Chinese, he’s also an immigrant to this country, to the US. His understanding of what it’s like to be Asian American, to have been here for several generations, is a little bit different. He doesn’t have that perspective.”

Salisbury was born in California and raised by a Chinese-American mother, which she says provides her with particular insight into Chinese-American identity and parentage. “I’m coming to this,” she declares, proudly, “as an insider.” This is reflected in her book, which continually hones in on Wong’s dual identity. Anna May Wong was born Wong Liu Tsong in 1905, renaming herself “Anna May” at the age of 11 after being given the name “Anna” by her family’s American doctor at birth. Both of the star’s parents were born in California, and expected their daughter to grow up to become a dutiful Chinese wife and mother. She was determined to carve out her own future, though. “Don’t think that I stray from my heritage lightly,” Wong once wrote. “It’s something I think about a lot. Am I taking the right path?” This uncertainty fascinates Salisbury. “She knows this is something she has to do – whether it’s something her parents want or not.”

Wong particularly scandalised her family in 1930, by not attending her mother’s funeral and choosing to continue work in a Broadway play – if she had returned home, she’d have been replaced in the show. Touchingly, her father kept her mother’s body in a vault until Wong was able to fly to Los Angeles. Later, in 1936, the pair put aside their differences and went on a tour of Chang’an, his ancestral village in China. They were followed by a documentary film crew, hired by the typically media-savvy Wong.

As Salisbury discusses this visit she suddenly stops. Visibly upset, she puts her hand over her heart. “You see them walking arm in arm through the countryside and he was so happy,” she says. “It’s hard. Wong’s conflicts with her father just remind me so much of my own relationship with my Chinese-American mother. Talking about Asian parents and expectations makes me get a little emotional... I feel I know very personally some of the things that Anna May felt. It’s hard to explain to people how you can be in conflict with your parent but still love them.” Salisbury’s eyes well up. “It is very emotional because you know that they want the best for you, but your definitions of what the best is are very different.”

Salisbury points out that, during the same trip to China, Wong was also under fierce pressure from the Chinese press. In one of the book’s most gripping chapters, Wong arrives on board the SS President Grant, only to have a mysterious, discombobulating encounter with a fellow passenger. As a result, Wong fumbled all the subsequent glad-handing, alienating the crowd of press and well-wishers to such an extent that there was a mini-riot (someone cried, “Down with Wong Liu Tsong – the stooge that disgraces China”). Wong was overwhelmed. All concerned got to see the normally poised Hollywood movie star covered in “tears and snot”.

“It gives you a sense of the impossible expectations that were put upon her,” says Salisbury. “People felt that she represented all of China. She was meant to humble herself, to give credit to her heritage. The press, during this visit, were so mean. They said things like, ‘Whether Anna May Wong can be counted as Chinese is still a question.’ They wanted to tear her apart!”

Just to be clear, America was always a hostile environment for Wong. Even after her return from Europe, she continued to be marginalised by Hollywood, getting passed over for parts that went to white actors in yellowface. Screen kisses with white co-stars were also forbidden. Off screen, she was reminded at every turn about who she could and could not marry. “Miscegenation, inter-racial marriage,” notes Salisbury, “was only made legal, in California, in 1948”. It could be done, but Wong’s fame made that option difficult. “For Wong to have married someone of another race would have caused a publicity frenzy.”

Wong was aware of all these cultural tensions and often wove them into her work. As part of a cabaret act that she performed throughout Europe in 1933, Wong sang the song “Half Caste Woman” by Noel Coward. “That song” says Salisbury, “is about a woman who’s half-Asian, half-white, who lives in a port Asian city and the only thing she’s good for is to be a prostitute for the foreign men who come in. I think that Wong viewed herself in that way; she was both things and not fully accepted in either arena.”

In 1940, Wong’s younger sister Mary, who was also an actress, died by suicide. For various reasons, including worries about work and money, Wong was soon drinking heavily and, in 1953, was diagnosed with cirrhosis. Researching this part of the book, says Salisbury, was “painful”. For a while, she even hoped to find proof that Wong wasn’t an alcoholic – “that the doctors got it wrong”. But no. “The smoking gun was a letter talking about a disastrous get-together with friends in New York,” Salisbury says. “It was in 1955, when she was about 50. She arrived so drunk they had to carry her out of the restaurant.” Wong died from a heart attack in 1961 at the age of 56.

Still, Salisbury doesn’t want to dwell on the negatives of Wong’s life. She’d rather focus on the star’s achievements. In the late Thirties, Wong insisted on being the lead in a number of pulpy crime thrillers, among them Daughter of Shanghai, where she and Korean-American actor, Philip Ahn (her gay, childhood friend), are the heroes. “Two Asian-American leads!” marvels Salisbury. “She really flipped the script. I don’t know if anyone at the time realised how revolutionary it was.” Salisbury also hopes readers will fall in love with Wong’s erudition (she wrote brilliant essays), her interest in current affairs (she was friends with the performer turned political activist Paul Robeson), as well as her wit. Wong once signed a publicity shot, “Orientally yours.”

In a planned biopic, Wong will be played by Gemma Chan, but Salisbury says she isn’t sure the star’s life can be accurately represented in a conventional film. “I don’t know how they’ll do it,” she says. “Gemma Chan is a little bit older. Anna May Wong started as a teenager, so it doesn’t seem realistic for Gemma to play those periods of her life… I don’t know if they’ll have a different actress for the early years.” She’s delighted that David Henry Hwang, who wrote the celebrated play M. Butterfly, is working on the script. “He’s like the foremost Asian-American playwright – I couldn’t think of a better person to write it.” That said, she doesn’t envy his job. “It’ll be very difficult to condense her life into a two- or three-hour film. I should know. I had trouble doing it in a book!”

Salisbury hasn’t got her own future mapped out (“maybe I’d like to write about mixed race identity in the US”). In case you’re wondering, Salisbury’s father is Irish-American, which creates its own issues. She doesn’t, it turns out, see herself as a true insider and says she’s “bracing” herself for awkward questions when she does face-to-face press. “I’m just waiting for someone to ask me, ‘Why did you decide to write this book if you’re not Chinese?’”

Salisbury’s book is about a woman who was forever being told she was too Chinese, or not Chinese enough. But despite all the hardships she faced, Wong always found a way to embrace her status as an in-betweener. After you’ve read Not Your China Doll, watch her films. Wong Liu Tsong was her own best creation and – even in her silent movies – somehow nabs the last word.

‘Not Your China Doll’ by Katie Gee Salisbury is published by Faber

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments