Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron – Portraits to Dream In review: they deserve shows of their own

Born more than a century apart, one a Victorian pioneer, the other an American who died young, these female stars of photography aren’t an entirely satisfying mix – but Francesca Woodman’s thrilling images steal the show

You could say that artists are a little like flavours – some work together, others don’t. Food journalist Nigel Slater once said, “You can’t really argue with the theory that if you like something then it works, but to experiment with marrying flavours, in a trial-and-error situation like a mad scientist, will not only take forever but will probably lead to some really horrid meals.” Now, I’m not suggesting this exhibition is horrid – on the contrary, there’s a lot to like – but to me the pairing of its protagonists isn’t satisfying.

Francesca Woodman (1958-81) and Julia Margaret Cameron (1815-79) are two of the most influential portrait photographers in art history. Cameron was British, working in Victorian England and then Sri Lanka, Woodman was American, working in Italy and the US. They lived a century apart. Both produced vast amounts of varied art during their brief, concentrated careers (Cameron started late, Woodman died young). Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: Portraits to Dream In at the National Portrait Gallery mixes more than 160 of their soft-focused, monochrome prints.

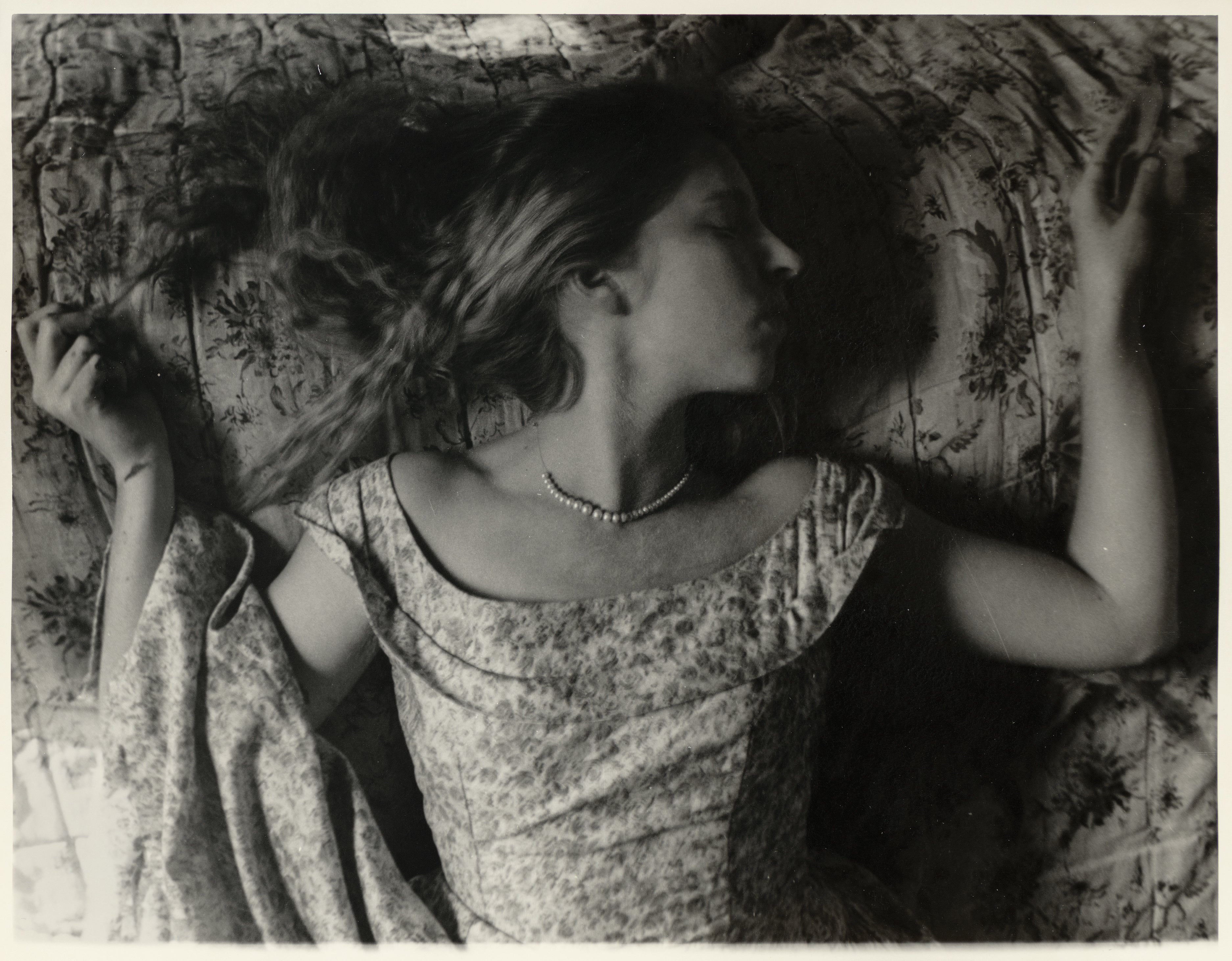

Borrowing its name from something Woodman said about photographs being “places for the viewer to dream in”, the show is small but pleasingly packed. At times the artists’ images are coupled to reveal thematic and formal similarities and differences, among them the presence of a brolly in bloom and blurry shapes achieved by slow shutter speeds. Elsewhere they mingle: a pale-blue wall is piled high with angels and otherworldly beings, Cameron’s cherubic with clasped hands and feathered wings, Woodman’s abstracted and unnerving (think lightning-like overexposure and suspended limbs).

Both artists took inspiration from Greek mythology and Arthurian legends, but where Cameron gives us fairly formal portraits of her sitters posing in costumes, Woodman’s practice is more performative. Inspired by the tale of the nymph Daphne transforming into a laurel tree in an attempt to escape the advances of the god Apollo, Cameron presents a dreamy beauty with a small posy of flowers, Woodman a lively sequence in a forest that resembles a set of film stills.

I kept having to remind myself, as I looked from one to the other, that Woodman was making work 100 years after Cameron – which explains why her subjects are more dynamic. Even her caryatids – partially draped women based on the sculpted female figures used instead of columns on Greek temples – can be viewed in light of the objectification of women. Cameron was moved to make painterly photographs by the Parthenon marbles, and those results are reasonably lovely, too, even if they do fail to move beyond an attention to cloth and classical proportions.

For me, the inevitable star of the show, and the reason I’d recommend you visit, is Woodman. Powerfully gifted, she began experimenting with photography as a young teenager before attending the Rhode Island School of Design, and the mostly untitled images she made in the 1970s, before she took her own life at 22, are thrilling and thought-provoking. Following hot on the heels of her 20th-century caryatids are intimate images that explore the female body in nature: a slender nude climbing an earthy riverbank, pale limbs becoming one with roots and leaves; a woman stretching out her arm, a mirror between water and sky, reflected pine trees seemingly sprouting from flesh-like wings.

The trouble with marrying them is that in comparison, Cameron, who first turned to photography in her late forties, can seem repetitive and unsurprising. Where Woodman plays with translucent swatches of fabric and silvery surfaces, creating double images that are off-kilter and casually provocative, verging on surrealist, Cameron shows us twinned girls that are cloying and sentimental. Her Pre-Raphaelite muses, all tumbling tresses and pillowy lips, are a tad too wistful for my liking.

A shame because she, too, is a pioneering photographer whose works are about more than faraway looks and muzzy edges. A case in point comes towards the end: her dramatically lit close-up of a rugged Italian male model dressed up as Shakespeare’s Iago is all light and dark, delicious bravado and deep introspection.

But in an exhibition that insists on comparing and contrasting, it’s impossible not to play favourites. From the start, I was marvelling at one more than the other, and by the end I found myself feeling frustrated with the enforced to-and-fro. Better, I think, to give the viewer the time and space to appreciate them as individuals, and each artist an exhibition of her own.

National Portrait Gallery, 21 March to 16 June

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments