Defending art can make you a co-conspirator in abuse – as the male cast members of Arrested Development show

There is a panic expressed by those with skin in the game, people who have made, championed or loved visual arts which now come with baggage, who fear that the baby will be thrown out with the bath water

I was talking to a colleague about Lukas Dhont’s Girl, the breakout sensation of Cannes, which won three prizes (Caméra d’Or, Queer Palm and Best Performance) for its observation-driven portrait of a 15-year-old transgender ballerina. My colleague, who had not seen the film, was voicing scepticism about a cis gender man, Victor Polster, being cast as a trans woman.

I leapt to the film’s defence, praising the empathy that saturates it and highlighting Dhont’s many stated reasons for this casting choice (which are on the record). I was feeling resentful of having to defend a film of such gleaming artistic calibre, and noticed that my casual tone was taking on a brittle edge.

This low key, hysterical defensiveness will be familiar to anyone who read The New York Times’ round table interview with the cast of Arrested Development.

Its ugliest moments – which went viral on social media – arise from New York Times journalist Sopan Deb following up on the revelations Jeffrey Tambor made to The Hollywood Reporter on 7 May about having a “blowup” on set with Jessica Walter.

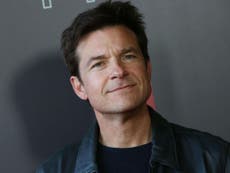

The male cast members instantly leapt to Tambor’s defence, led by a garrulous Jason Bateman, who used a range of psychologically pressurising techniques to minimise Walter’s emotional reaction. His motor-mouthed whirlwind included saying “not to belittle you” three times (while belittling her) and explaining Walter's own profession to her (“It’s a weird thing, and it is a breeding ground for atypical behaviour and certain people have certain processes.”)

Jessica Walter was still so raw about the experience that she recollected it through her tears.

The full transcript, and accompanying audio extract, goes beyond the dynamic of this cast of characters, crystallising the fault lines of a battle taking place in different guises across the film and television industry as a whole. In the wake of MeToo, we have been reckoning with what to do with previously exalted works, now proven to have been made with help from abusers. There is a panic expressed by those with skin in the game, people who have made, championed or loved visual arts which now come with baggage, who fear that the baby will be thrown out with the bath water. They fear that their personal favourites from the established canon will be locked in a vault and left to rot in obscurity.

This paranoia has led to some cinephile purists proudly refusing to let accounts of criminal behaviour affect their cinematic reads: “I knew that Harvey Weinstein was a sexual gangster,” wrote the director Paul Schrader in an October 2017 Facebook post, “That wasn’t what offended me about the man.”

On the flip side, there are also activist critics who proudly refuse to let the artistic value of a work affect their account of it after wrongdoings on the part of the maker emerges. The single word “cancelled!” has become a normalised social media way of trashing everything that a once beloved icon stood for, as if doing so will save the day, as opposed to pushing away those who might be reached by a more considered response.

The way that we interact with art as consumers is an intensely personal matter. Cinema and television can often serve as a social surrogate to lonely people, who commune with it like their souls depends on it. Glib dismissals of work can just serve to alienate these fans.

However, those who have human connections and, yes, belittle them in the name of elevating art are guilty of perpetuating a fallacy that – at the most low-stakes end – can lead to fleeting tension in a discussion with a colleague, but at the highest-stakes end can be used to dismiss aggression, abuse and criminal harm.

Jason Bateman and Tony Hale have since bowed under the weight of public pressure and taken to Twitter to apologise, but a truer test of their sincerity will come from how they proceed to weigh the matter of people against art.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies