Anthony Grey: Hostages need action, not pussyfooting

One high-profile former captive says the world must confront the growth of kidnapping, while diplomats favour a low-key approach

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Few people can have gone through last week not having heard the name Linda Norgrove. The senior aid official died, in circumstances still unclear, having been kidnapped in northern Afghanistan. But have you ever heard of Hervé Ghesquière or Stéphane Taponier? I doubt it. Something of a journalistic blind spot seems to exist in the UK and internationally, as far as they are concerned. They urgently need the sort of publicity that surrounded the kidnapping, and more importantly the death, of Linda Norgrove.

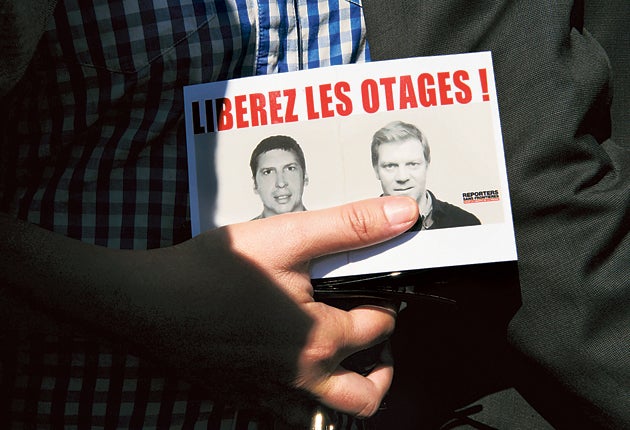

Both men, experienced war correspondents in their early forties, have today been held hostage under constant of threat of death for 290 days by Afghan insurgents fighting the Nato coalition in the mountains north-east of Kabul. With them are three Afghan assistants. But curiously, the two TV reporters have received very little media coverage and attention outside of France – and not much even in their own country. President Nicolas Sarkozy distinguished himself soon after their capture on 30 December 2009 by stating angrily through his chief of staff that the pair had behaved with "a palpable lack of care" by entering a zone where Taliban and other hostile insurgents are active. "You don't go for a scoop at any price," he commented.

French broadcasting representatives condemned the Elysée Palace's attitude as "a disgrace". Agreed. Nearly six months of near media silence passed before a video of Hervé and Stéphane was placed on a Jihadist website in April, saying they would be executed very soon if Taliban and other insurgent prisoners in Afghan jails were not released. For some reason it made no real international impact. And I discovered the journalists' plight for the first time only on a recent visit to France. On checking and finding there had been only vestigial coverage of their case to date in Britain, I recalled that my own solitary incarceration as a hostage in China in 1967-69, when I was a Reuters correspondent, had been covered comprehensively in the French press. Admittedly I was arguably the first international political hostage of modern times, a dubious privilege.

But feeling conscience-stricken, I wrote an immediate email to the parents of the two Frenchmen, asking if they felt enough was being done by their national and world media, their government and employers. I also wrote in a similar vein to the Washington-based Campaign to Protect Journalists. But there was still very little reaction. Compassion fatigue seems to have set in around the fate of hostages worldwide.

But to its great credit, the IoS when I approached them with this information, decided to take a broader, deeper look at the subject – and the resulting investigative article (on pages 29-31) reveals the true scale of the extraordinary expansion of the practice of hostage-taking and kidnapping worldwide in recent times. It has become vastly commercialised also, particularly in and around Somalia, virtually becoming an international industry. Clearly a distinction remains between ransom-seeking pirates and land-based kidnappers and others, such as the Taliban in Afghanistan, who seek world attention for political ends.

Dealing with hostage situations of all kinds is difficult for all concerned. There are no simple solutions. The conflict between seeking publicity or not is almost always fraught with fierce argument and indecision. In my case, the Foreign Office in London advised the British and international media generally to eschew all publicity – and this was largely respected, even by my employers, Reuters, a leading world news agency, for some 18 months. Then the dam broke, and an intensive worldwide campaign by the media and journalism organisations followed. I was freed eight months later. So I would always seriously question official requests to "play it down, old boy" since this, first and foremost, best serves the interests of officialdom.

Six months after the capture of the two French TV journalists, big banners bearing the photographs of Hervé and Stéphane were at last hung on local public buildings in Bordeaux and Nantes, their home cities and in the Luxembourg Gardens in Paris. The organisation Reporters Without Borders (www.rsf.org) took full page adverts in some newspapers reading: "Hervé and Stéphane have been held now for six months. React!" All of us now reflect urgently on how we might best "react".

Should not Nato, as the key organisation in the field in Afghanistan, set up some continuing public channel of action? Is it time the UN considered instituting some kind of office or continuing programme for dealing with the constantly recurring worldwide activity of hostage taking ? This awful practice has gone on throughout human history and seems unlikely ever to go away. Following Linda Norgrove's death, we heard of the Save the Children consultant in Somalia. The Somali-style land and sea kidnapping industry has clearly taken the practice into a new dimension. The UN ought to acknowledge this – we could target the Secretary General with requests. Nearly a million merchant seamen have recently done just that, signing a petition directed to the UN Maritime Agency appealing for action.

Perhaps organisations such as the International Federation of Journalists which represents 600,000 trade unionists in 120 countries, should also now raise its professional voice on behalf of our two sorely afflicted colleagues Hervé and Stéphane. And how might we "react" as individuals? During my time in China, British newspapers appealed to readers to send me postcards and Christmas cards: thousands responded, not just from Britain but also from Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the US and elsewhere. I never received any of them, of course. The Chinese authorities are said to have been forced to burn the cards "by the sackload". Eventually the Chinese government was embarrassed by worldwide moral concern for an innocently imprisoned individual.

What might be the equivalent of this in our more advanced internet age? Emails to the Campaign to Protect Journalists (info@cpj.org) or France 3 TV (www.France3.fr) to be passed to the families of the two men. Emails to the other organisations I have mentioned. It would be a simple way of expressing our humane support and understanding for the two brave French reporters and their relatives. That sort of action was very important to me when I discovered it, and helped greatly in restoring my faith in human nature when I finally emerged from the prolonged trauma.

Anthony Grey tells the story of his solitary confinement in The Hostage Handbook (The Tagman Press: www.tagmanpress.co.uk)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments