Scientist who pioneered 'three-parent' IVF embryo technique now wants to offer it to older women trying for a baby

Exclusive: The doctor who pioneered the technique is pushing for it to be used for infertility in older women, raising hopes for millions. But its use beyond those suffering from mitochondrial diseases will provoke an ethical storm

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Older women trying for a baby could soon be offered the IVF technique of so-called “three-parent” embryos that would help families with serious mitochondrial diseases to have healthy children, and which won the backing of MPs last week.

The US scientist who pioneered the technique of mitochondrial transfer has applied for permission to use it as a fertility treatment for women who, because of their age, have difficulty becoming pregnant naturally or by conventional IVF.

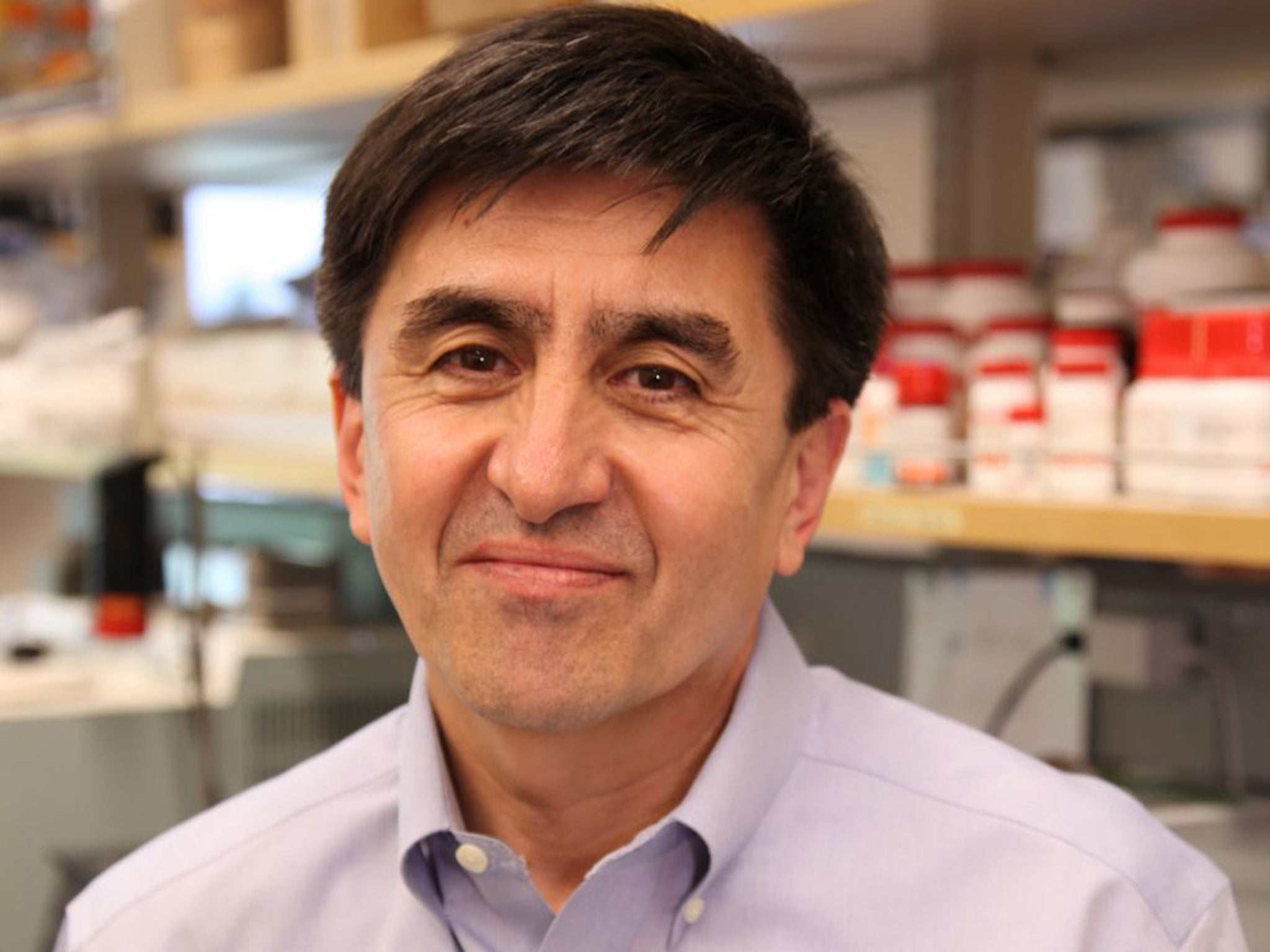

Dr Shoukhrat Mitalipov, a world authority on embryo manipulation, said he had requested permission from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to conduct trials of mitochondrial transfer as a treatment for age-related infertility. He said the parliamentary vote last Tuesday, when MPs overwhelmingly approved the “three-parent” baby technique for creating IVF babies free of mitochondrial disease, has bolstered his case with the US regulator.

“We hope it will help in the US, and hopefully the FDA will move faster. The families have heard about the UK outcome and they welcome it. We’re very excited by it,” said Dr Mitalipov, senior scientist at the Oregon Health and Science University in Portland.

“Compared to a rare condition like mitochondrial disease, infertility is a big, big problem for modern society because of women delaying their first baby. When they finally decide, the delay has already affected their egg quality,” he said.

The development will be controversial, and there may be considerable demand for the treatment because, unlike conventional egg donation, it enables a woman to have her own genetically related child. Before the free Commons vote on Tuesday, there were impassioned arguments against the procedure on the grounds that allowing it to be used in the case of a serious genetic disease was the start of a slippery slope that could lead to genetically modified “designer babies”.

Although the proposed British legislation only applies to women carrying serious mitochondrial disease, the possibility of the technique being used in the US as an infertility treatment could prompt calls for it to be used here to help women aged over 35 become pregnant.

“The procedure is identical to mitochondrial disease treatment,” Dr Mitalipov said. “It has to be shown we can improve the pregnancy outcomes for these patients, and we are looking forward to doing the clinical studies with older women.

“We consider infertility a disease, and you treat the patients as you do for mitochondrial disease. I wouldn’t say one disease is more severe than another. Infertility is a very serious problem and these women deserve treatment as for any other disease. If the procedure is effective and safe, why would you hold it for one group of patients, but not for another?”

John Harris, professor of bioethics at Manchester University, said that if mitochondrial donation were shown to be safe for women who want IVF babies free of mitochondrial diseases, then it would be hard to argue against its application to infertility in older women.

“If the technique is safe enough for it to be used for the one purpose, I don’t see why it wouldn’t be safe enough to use for the other,” he said.

“A lot of the objections to the use of mitochondrial transfer are to do with the slippery-slope arguments. Objectors say once you start making alterations, even a very tiny part of the mitochondria, then this will open the door to more radical genetic engineering and designer babies.

“But that objection would not apply to this case. It could not be argued this is further down a slippery slope for the simple reason the slippery slope applies to the extension of the technique, not to the use of the same technique for another therapeutic purpose – and treating infertility is recognised as a therapeutic purpose,” he explained.

“It’s not about extending the technique to make more radical changes to the DNA. It would be the same change to the DNA of the individual but for a different purpose, and it’s a therapeutic purpose. It would be like saying you can use antibiotics to treat one kind of infection, but not other kinds of infection.”

But the Labour MP Frank Dobson, a former health secretary who spoke passionately in favour of legalising mitochondrial donation in the Commons, said he would find it hard to support its wider use as a general fertility treatment. “Mitochondrial donation is about children who are going to die. It’s a much more sympathetic case than using it for older women who want to have children,” he said.

Professor Mitalipov, who has a distinguished record in reproductive science, said there is strong evidence that women become less fertile after 35, because of the ageing of the egg cytoplasm, the non-nuclear part of the egg that is replaced during mitochondrial transfer.

“We’ve always wondered why women of this age have eggs that are not capable of developing into viable pregnancies. It all points to the egg quality,” Professor Mitalipov said.

“Some say it’s a nucleus problem. Others say it is mainly a cytoplasm problem, due to the maturation of the egg. If that is true, then replacing the cytoplasm with the egg cytoplasm of a younger woman should resolve this issue of egg quality.

“We’ve been pursuing basic studies and everything points to that, and we know this can be circumvented by the replacement of the cytoplasm.”

Professor Mitalipov, who has advised Britain’s Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA) on mitochondrial transfer, confirmed he has applied to the FDA for two clinical trials licences, one for treating mitochondrial disease, the other for treating age-related infertility.

“It’s all one package,” he said. “We use the same treatment for mitochondrial disease patients, and, separately, another trial will be for women of advanced age.

“They may approve one procedure first and then a second. That’s my expectation,” he said. “So far we haven’t heard anything from the FDA on the specifics of how they want us to run this clinical trial. My sense is that they want to take the route that the HFEA did.

“They want to maybe look first into ethics,” he added. “I think we’re talking of another year of delay.”

In the UK, if the Lords approves the amendment to the 2008 Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act, the HFEA will be allowed to issue a licence after October, when the law takes effect. The first mitochondrial-disease licence is likely to be awarded to Newcastle University where scientists are hoping to create the first “three-parent” embryo later this year, with the first birth in 2016.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments