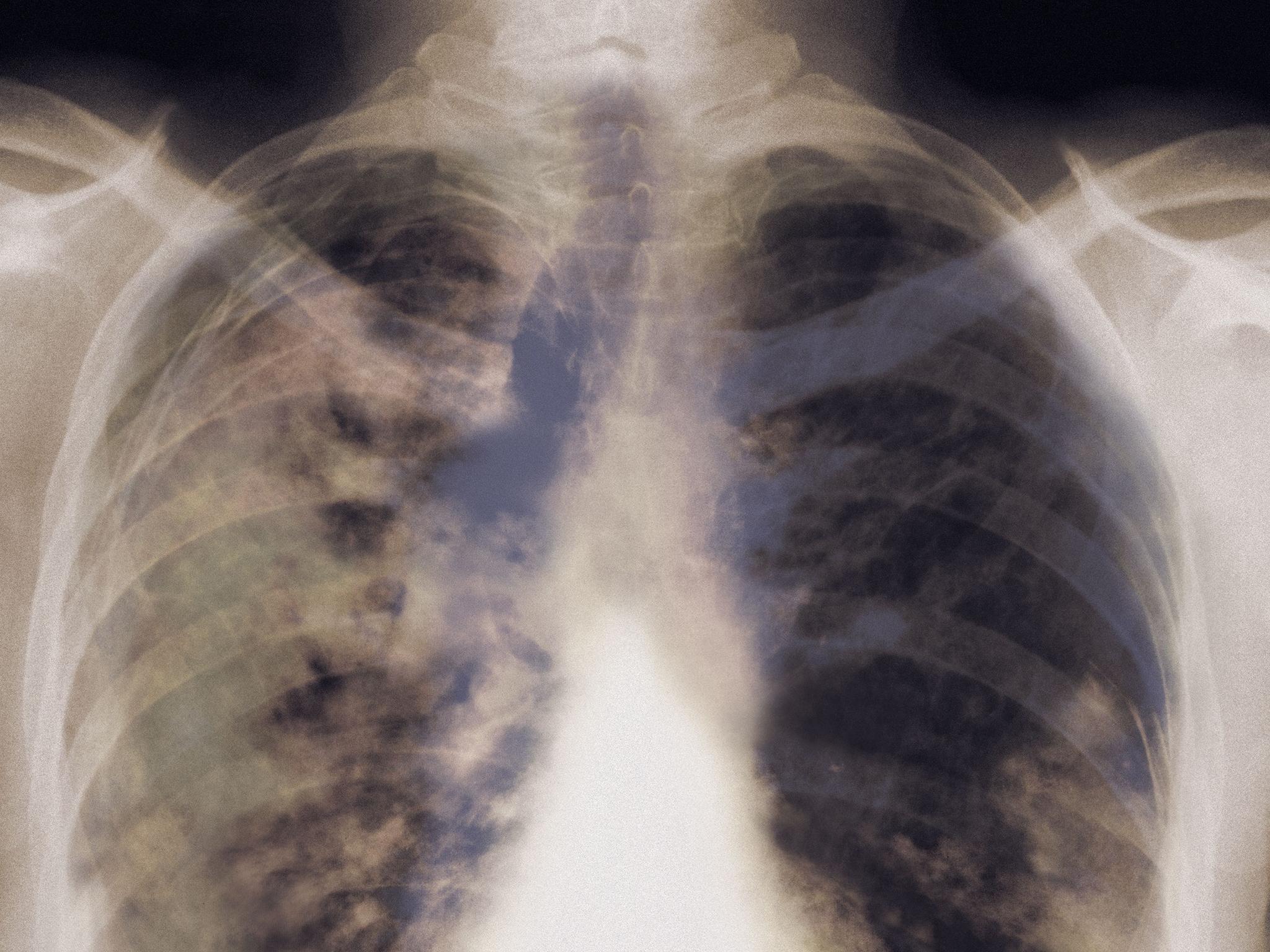

Lung cancers can 'lie dormant' in ex-smokers for up to 20 years before they become aggressive

The researchers carried out a genetic analysis of the tumour cells from seven lung-cancer patients and found a surprising variation within each tumour

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Lung cancers in ex-smokers can lie dormant for as long as 20 years before they begin to grow into a life-threatening tumour, a study has found.

Scientists found that the original mutations in lung cells caused by inhaling cigarette smoke can date back many years before additional mutations cause them to become aggressive cancer cells.

The researchers carried out a genetic analysis of the tumour cells from seven lung-cancer patients and found a surprising variation within each tumour in terms of the DNA mutations that triggered the disease.

Lung cancer has a low rate of survival, with just 10 per cent of patients still being alive five years after diagnosis and being able to understand the genetic evolution of tumour cells will help to improve treatments, scientists said.

“Survival from lung cancer remains devastatingly low with many new targeted treatments making a limited impact on the disease,” said Professor Charles Swanton at Cancer Research UK’s London Research Institute and UCL Cancer Institute.

“By understanding how it develops we’ve opened up the disease’s evolutionary rule book in the hope that we can start to predict its next steps,” said Professor Swanton, who led the study published in the journal Science.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments