The Book List: Meet Sir John Lubbock, Godfather of the must-read listicle

Every Wednesday, Alex Johnson delves into a unique collection of titles. This week he looks back at an MP’s musings that got the ball rolling

The Bible

The Meditations of Marcus Aurelius

Epictetus

Aristotle’s Ethics

Analects of Confucius

St Hilaire’s Le Bouddha et sa religion

Wake’s Apostolic Fathers

Thomas à Kempis’s Imitation of Christ

Confessions of St. Augustine (Dr Pusey)

The Koran (portions of)

Spinoza’s Tractatus Theologico-Politicus

Comte’s Catechism of Positive Philosophy

Pascal’s Pensées

Butler’s Analogy of Religion

Taylor’s Holy Living and Dying

Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress

Keble’s Christian Year

Plato’s Dialogues; at any rate, the Apology, Phædo, and Republic

Xenophon’s Memorabilia

Aristotle’s Politics

Demosthene’s De Corona

Cicero’s De Officiis, De Amicitia, and de Senectute

Plutarch’s Lives

Berkeley’s Human Knowledge

Descartes’s Discours sur la Méthode

Locke’s On the Conduct of the Understanding

Homer

Hesiod

Virgil

Epitomized in Talboys Wheeler’s History of India, vols i and ii:

Maha Bharata

Ramayana

The Shahnameh

The Nibelungenlied

Malory’s Morte d’Arthur

The Sheking

Aeschylus’s Prometheus

Trilogy of Orestes

Sophocles’s Oedipus

Euripides’s Medea

Aristophanes’s The Knights and Clouds

Horace

Lucretius

Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales (Perhaps in Morris’s edition; or, if expurgated, in C Clarke’s, or Mrs Haweis’s)

Shakespeare

Milton’s Paradise Lost, Lycidas, and the shorter poems

Dante’s Divina Commedia

Spenser’s Faerie Queen

Dryden’s Poems

Scott’s Poems

Wordsworth (Mr Arnold’s selection)

Southey’s Thalaba the Destroyer, the Curse of Kehama

Pope’s Essay on Criticism

Essay on Man

Rape of the Lock

Burns

Byron’s Childe Harold

Gray

Herodotus

Xenophon’s Anabasis

Thucydides

Tacitus’s Germania

Livy

Gibbon’s Decline and Fall

Hume’s History of England

Grote’s History of Greece

Carlyle’s French Revolution

Green’s Short History of England

Lewes’s History of Philosophy

Arabian Nights

Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels

Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe

Goldsmith’s Vicar of Wakefield

Cervante’s Don Quixote

Boswell’s Life of Johnson

Molière

Sheridan’s The Critic, School for Scandal, and The Rivals

Carlyle’s Past and Present

Smiles’s Self-Help

Bacon’s Novum Organum

Smith’s Wealth of Nations (part of)

Mill’s Political Economy

Cook’s Voyages

Humboldt’s Travels

White’s Natural History of Selborne

Darwin’s Origin of Species

Naturalist’s Voyage

Mill’s Logic

Bacon’s Essays

Montaigne’s Essays

Hume’s Essays

Macaulay’s Essays

Addison’s Essays

Emerson’s Essays

Burke’s Select works

Voltaire’s Zadig

Goethe’s Faust, and Autobiography

Miss Austen’s Emma, or Pride and Prejudice

Thackeray’s Vanity Fair

Pendennis

Dicken’s Pickwick

David Copperfield

Lytton’s Last Days of Pompeii

George Eliot’s Adam Bede

Kingsley’s Westward Ho!

Scott’s Novels

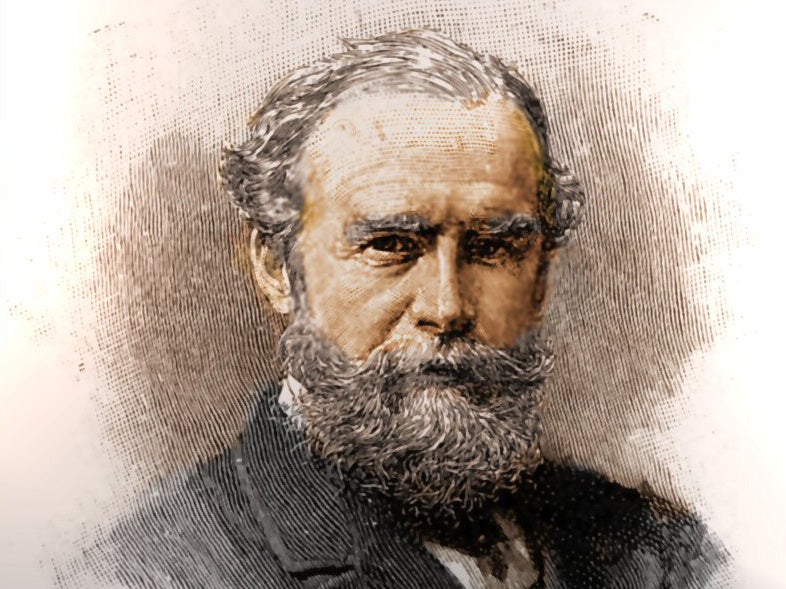

Wherever you look there are endless listicles of the “1,001 Novels You MUST Read Before You’re 40” variety. We have the Godfather of the Best Books List to thank for setting this hare running: banker and philanthropist Sir John Lubbock (1834–1913). Though all but forgotten today, Lubbock was an important man, the MP responsible for introducing the Bank Holidays Act (1871), and as principal of the Working Men’s College in London, he gave a speech in 1886 in which he listed 100 books.

“I drew up the list,” he said, which excluded living authors, “not as that of the hundred best books, but, which is very different, of those which on the whole are perhaps best worth reading.” It was then published and became a bestseller, with a knock-on effect on the books mentioned. It is printed above, and in the order he listed the titles. His top 100 (which appears to be more like 100-ish on close inspection) was organised by category, eg philosophy, travel, history, but he was wary about a “science” section on the basis that “science is so rapidly progressive”.

Also, it is important to note that these were not personal favourites. “As regards the Shi King and the Analects of Confucius, I must humbly confess that I do not greatly admire either; but I recommended these because they are held in the most profound veneration by the Chinese race.” Following close on Lubbock’s coattails was Dean of Canterbury and Marlborough headmaster Frederic William Farrar, who wrote a series of monthly articles for The Sunday Magazine in 1898 along similar lines, though with rather more literature. But not everybody was a great fan of the concept. Oscar Wilde wrote to The Pall Mall Gazette in 1886 that a more important list would be the Worst Hundred Books, so readers would know what to avoid. He then suggested dividing books into three classes:

Books to read:

Cicero’s Letters, Suetonius, Vasari’s Lives of the Painters, the Autobiography of Benvenuto Cellini, Sir John Mandeville, Marco Polo, St Simon’s Memoirs, Mommsen, and Grote’s History of Greece.

Books to reread:

Plato and Keats

Books not to read at all:

Thomson’s Seasons, Rogers’s Italy, Paley’s Evidences, all the Fathers except St Augustine, all John Stuart Mill except the Essay on Liberty, all Voltaire’s plays without any exception, Butler’s Analogy, Grant’s Aristotle, Hume’s England, Lewes’s History of Philosophy, all argumentative books and all books that try to prove anything.

Philip Waller in his excellent book Writers, Readers and Reputations: Literary Life in Britain 1870–1918 writes that these kinds of “best books” lists seem to some people like a “chronic exercise in futility”.

‘A Book of Book Lists’ by Alex Johnson, £7.99, British Library Publishing

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies