Kazuo Ishiguro, appreciation: The Nobel Prize-winner's approach to the English language is of a connoisseur, a collector

Andy Martin hails the award-winning novelist, one whose works have carved out a distinctive identity in British literature

Most writers sit about feeling that they were robbed when they don’t get it; Kazuo Ishiguro is probably the first writer, when he was told that he had been awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, to suspect that it was some kind of hoax. The same modesty is characteristic of him both as a writer and as a man.

I had the pleasure of meeting him once at the offices of Faber and Faber, who had just brought out The Remains of the Day, perhaps his best-known work, which went on to win the Booker Prize in 1989.

“Hello, Mr Ishiguro.”

“‘Ish, please.”

“I loved your book.”

“Oh, it was nothing. But I have been reading your book.”

He wanted to talk about my work, not his own. Ishiguro can be compared, as regards his acquisition of the English language, to Joseph Conrad or Vladimir Nabokov. Like them he came at the language which would become his raw material from the outside. He doesn’t act as if he truly owns it. He is merely looking after it for a while, admiring it and polishing, and there is a proportionate care and precision in his treatment of words. Irrespective of the story he is telling, there is a poetic sensibility at work.

Ishiguro was born in 1954 in Nagasaki to Japanese parents. But the family moved to England in 1960 when his father got a job as an oceanographer in Surrey. When his butler protagonist Stevens in The Remains of the Day takes a road trip around the countryside of England, admiring the moderation of both climate and landscape, it is like Ishiguro himself taking a tour around the English lexicon. The author became a British citizen in 1982 but his approach to the language and the culture remains that if not of an outsider than certainly a connoisseur, a collector.

The making of Ishiguro as a writer was undoubtedly the University of East Anglia and the creative writing MA presided over by Malcolm Bradbury and Angela Carter. His “dissertation” went on to become his first novel, A Pale View of Hills (1982). He was elevated to the realm of Granta Best Young British Novelists even before publishing An Artist of the Floating World (1986), which won the Whitbread Prize. Both of these first two novels have strong Japanese elements: in the first a Japanese woman, transplanted to England, is trying to come to terms with the suicide of her daughter. The second is actually set in Japan, in the post-Second World War environment, but it is a largely imaginary world, a tissue of memories and ideas, largely taking place in the head of the narrator/artist, Ono.

What immediately stood out about Ishiguro’s work was his stylistic minimalism, the kind of writing that Barthes characterised as “degree zero”. The austerity of style is often mirrored in the restraint and self-containment of the characters. Stevens, for example, never follows through on his passion for the housekeeper Miss Kenton out of a sense of duty. Obliqueness is combined with subjectivity in his narrators.

Ishiguro graduated from the University of Kent with a degree in English and philosophy and there remains a certain metaphysical dreaminess to his writing. The Nobel judges praised his work for revealing “the abyss beneath our illusory sense of connection to the world”. Ishiguro is an anti-naturalist. He doses out delicate materialist details, almost out of respect for the texture of more classically realist narratives, but there is always a certain haziness or indeterminacy hanging over the truth-value of any descriptions. Nothing is quite what it seems at first glance. Dreams, delusions and deceptions predominate.

Ishiguro’s habitual use of the first-person narrator is exemplary of his epistemology. There is no “omniscient narrator”. Narrators are limited in their range of sympathies and knowledge of the subject that is at the core of his story. Philosophically speaking, Ishiguro approaches the classic British empirical stance in a spirit of scepticism. When you think you know, you don’t know. He who knows does not speak, he who speaks does not know.

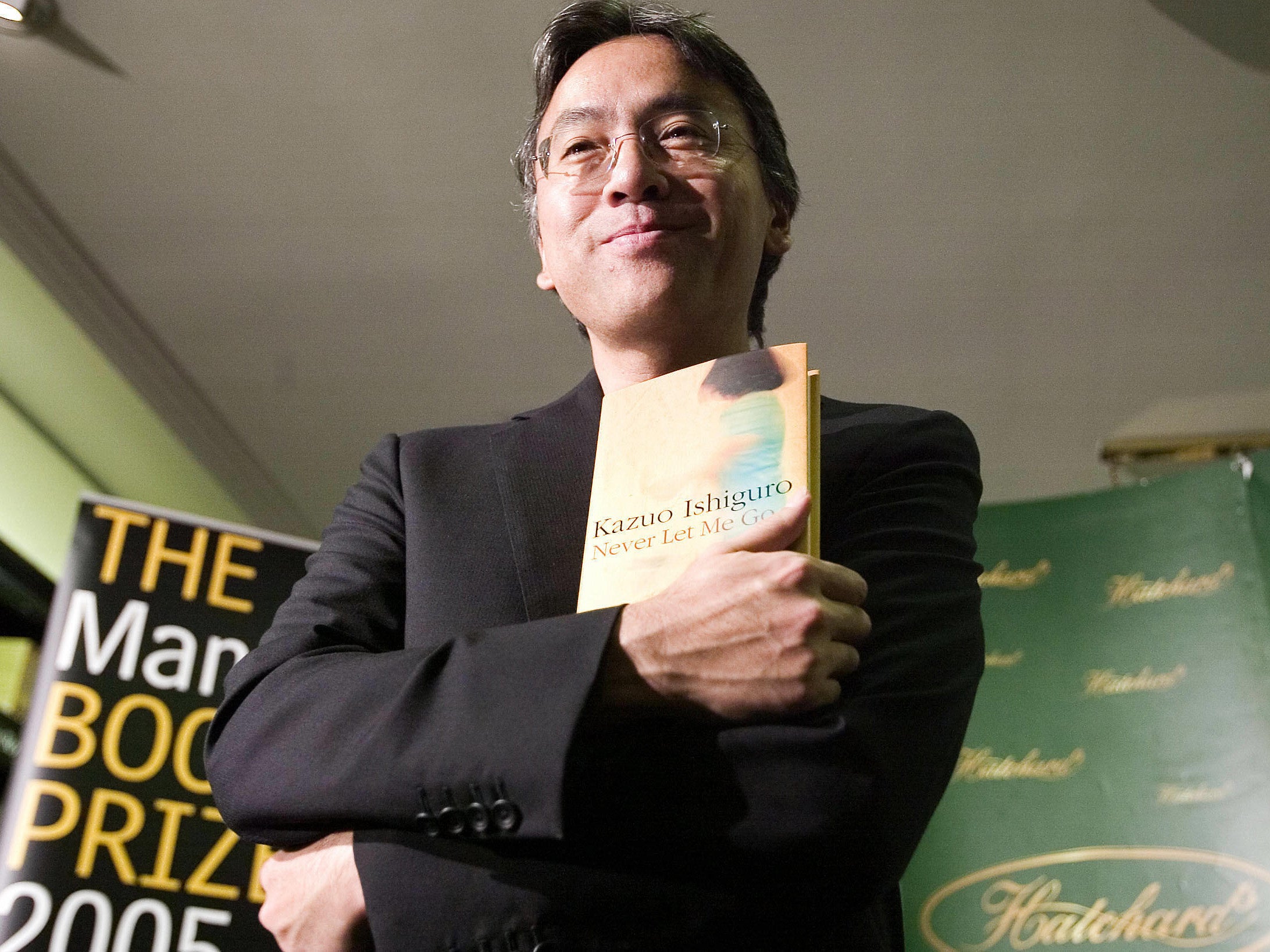

This gradual revelation of a state of ignorance underpins Never Let Me Go, named by Time magazine as the best novel of 2005. The novel is a hybrid of horror, science fiction and coming-of-age narrative, darkly populated by cloning and involuntary organ donation.

The Buried Giant, Ishiguro’s most recent work, represents another swerve in his trajectory, delving, perhaps allegorically, into the distant past of Arthurian Britain, with sword and sorcery, and introducing a third-person omniscient element for the first time. But what persists is the sense that, as one of his characters says, “the mist covers all memories, the bad as well as the good”.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies