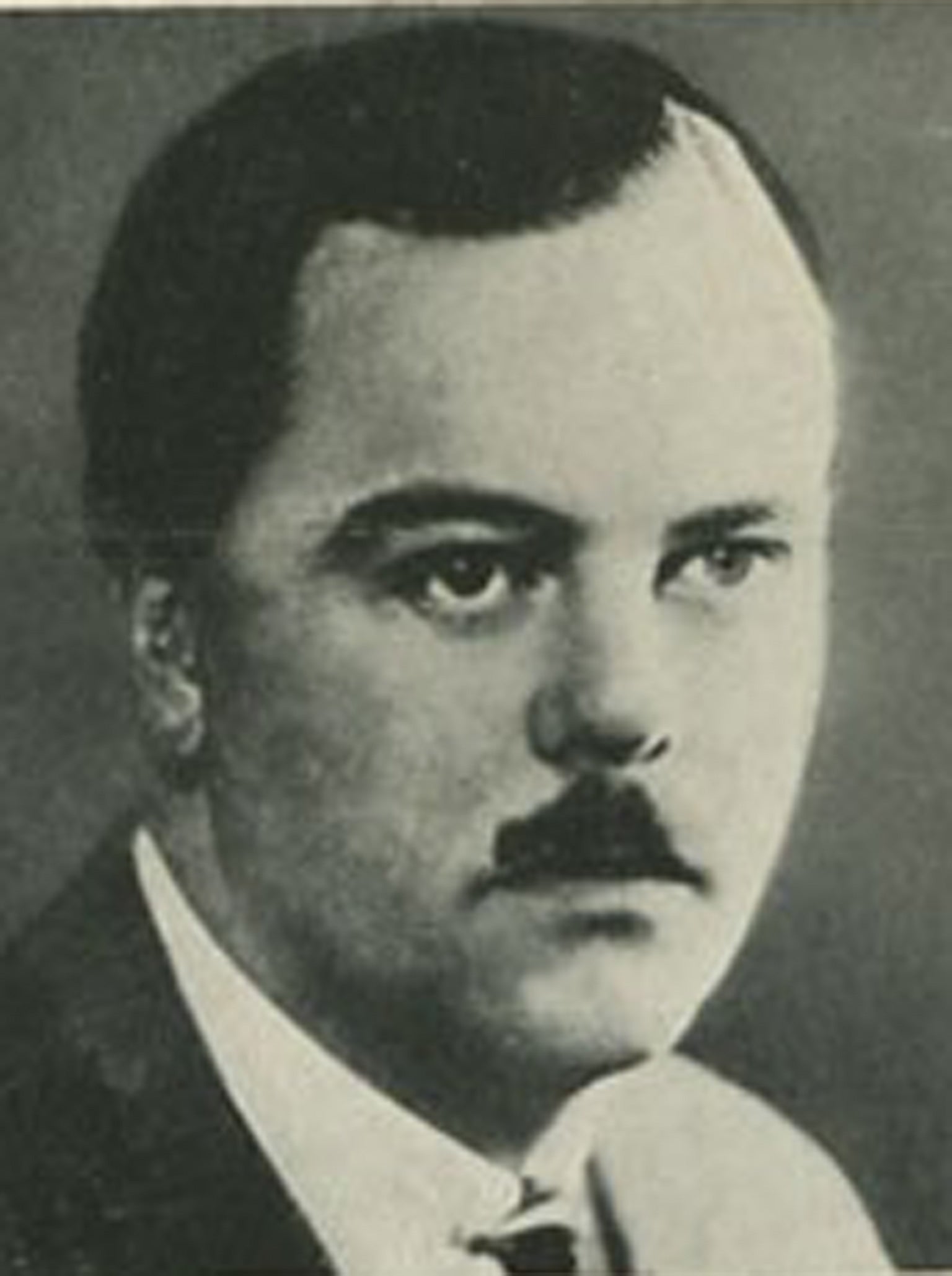

Invisible Ink: No 150 - Anthony Berkeley Cox

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Sometimes it's not just authors who go out of fashion but the style of novels themselves. Collaborative novels were produced by the Detection Club, with each member writing a chapter, and one author selected for the unenviable task of tying up all the loose ends. Anthony Berkeley Cox was one of crime fiction's greatest innovators, and its least remembered. He organised the dinner meetings that led to the club's foundation, and had the temerity to parody Dorothy L Sayers' Lord Peter Wimsey in its second collaborative novel, Ask a Policeman, something for which the grand lady took a long time to forgive him.

Cox was born into affluence in 1893 (he was related to the Earl of Monmouth) and served in the Army during the First World War before becoming a journalist. His first novel was published anonymously. He then began writing unusual novels under a number of pseudonyms. The Wychford Poisoning Case took a number of facts from the famous Florence Maybrick arsenic poisoning and explored it by adding psychological insight. He said: "Every detective must be a psychologist, whether he knows it or not."

More interested in the path leading to criminal behavior than the whodunnit aspect, Cox took the approach to its zenith in The Poisoned Chocolates Case by having six armchair investigators come up with six separate plausible solutions to the mystery. Under the name of Francis Iles he wrote his finest pair of novels, in which the outcome is revealed in the opening lines. In Malice Aforethought, we follow Dr Bickleigh setting out to kill his wife, and in Before the Fact, we're told that heroine Lina will discover her husband Johnny is a murderer. In the latter, suspense escalates as Lina finds clues to Johnny's behavior – his gambling, his stealing – and gives him the opportunity to explain his actions. Johnny is so charismatic that he always has a plausible ready excuse, and despite everything, still brings light into her life. The tension lies in wanting to know how long it will be before she ceases to be blindsided by him; before the book's utterly devastating final chapter explains the true nature of victimhood. It was filmed by Alfred Hitchcock as Suspicion (with the famous glowing glass of milk but a much weaker script) and has now been reprinted by Arcturus Press.

'Invisible Ink: How 100 Great Authors Disappeared' by Christopher Fowler is published on 19 November 2012 (Strange Attractor Press, £9.99)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments