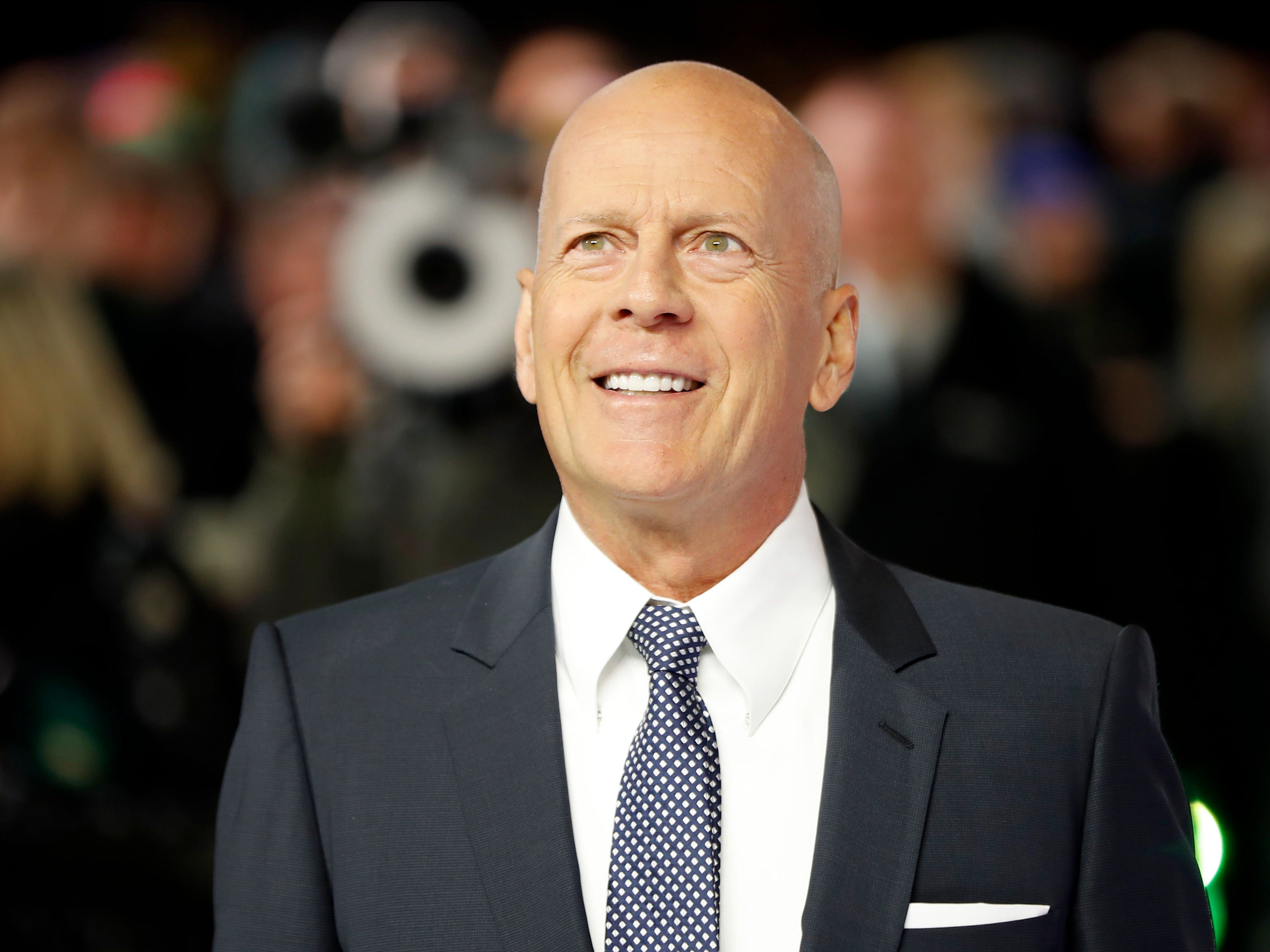

Like Bruce Willis, my dad got a terrifying diagnosis. I ended up knowing him better

Because of his condition, my dad often seemed like he wasn’t responding to the ‘real world’. He said what he thought in public, sometimes making his family flinch. He formed unusual clay pitchers and figurative pots; he started writing poetry

“It was crushing for anyone who wanted to express themselves, who wanted to be heard and couldn’t. It was frightening,’’ said Bruce Willis in his biography, describing his early years with a stutter.

Willis was an actor who began his career onstage as a child to escape the stigma of his language condition. Now he is an adult exiting that stage to face another condition that impedes his use of language— aphasia. As Willis’s family shares the news of his retirement from the silver screen due to his condition, I feel the need to point out that Willis is still valuable even if we don’t get to see him starring or directing a new movie. The media discusses his net worth, and everyone bids him goodbye on Twitter while chronicling the horrors of his illness. And though those who memorialize him likely have great intentions, it’s no wonder he and his family felt they needed to hide his illness for so long. They understood that those who suffer with conditions that affect language, memory, and speaking are stigmatized. And this stigma can debilitate the very people who are already struggling.

“It is lonely out here. We do not lose our brains all at once,” my dad once said to me before he lost most of his words. He is a former American naval officer, CEO, product designer, sailor, and author who once carried a shiny briefcase everywhere, talking about work constantly. Now he has forgotten who I am or the word for ‘‘sunshine’’ due to his Alzheimer’s.

Yet as his job titles are forgotten and his language skills weaken, I can see that something precious about him stays intact. When I watch my dad’s hollowing sea-grey eyes and scan his lips for the sign of a word, I feel like a girl on the boat beside him, looking for the horizon she could never quite see. He was hard to know even though we worked and sailed together. He was intense; addicted to the rat race, achievement and alcohol; with fluctuating moods that were tied to pleasing clients and earning paychecks. But now I recognize someone I couldn’t see back then.

‘‘Did you know my friend with Alzheimer’s killed himself?’’ my dad repeated to me years ago almost every time I talked to him. He had already been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. And his first good friend with the condition had taken his own life. This terrified both of us.

What my dad did next made me more proud than any of his past accomplishments. Along with my mom, he sought help, resisting the downward plummet and stigma of his disease. He started to openly advocate not just for himself, but for others, joining my mother on walks and during public speaking engagements with the Alzheimer’s Foundation.

Because of his condition, my dad often seemed like he wasn’t responding to the ‘‘real world.’’ He said what he thought in public, sometimes making his family flinch. He formed unusual clay pitchers and figurative pots; he wrote and spoke incessantly about his own dad. He scribbled poems daily, mailing them to most of the family. He visited me in Switzerland, climbed the Alps, and helped random people in hotels with suitcases, not minding if he seemed a tad odd. He talked to every dog and cat he saw and wrote excessive letters as well as the poems, not expecting anything back, but sending me and others little pieces of his mind he hoped we might preserve.

Meanwhile, my mother — also a writer and artist — joined him in his exploits, protecting his dignity by surrounding him with creative activities including trips to a pottery studio, a singing group, and long walks in nature. She coped by keeping busy, publishing Dad’s poetry chapbook, displaying his pottery, and even helping him send passionate and sometimes furious letters to politicians. She helped him decorate his office with images of his children, his naval ship knot collection, his antique pens, and the interior design books he published with her. When I recently visited him, I walked into his office and felt as if I was entering the ocean of his mind for the first time. Though he had few words remaining, I thought I understood a part of him that language couldn’t capture.

Now my dad carries the old briefcase that he once clutched beside me when we rushed to his office for a meeting. It is no longer shiny, but a bit dingy, decorated with star stickers, images, and words he has pressed onto the surface to help him remember who he is. “Adult man, poems, journalism, and more…’’ the case reads as he swings it beside him on the way to the memory care facility. Inside, his case is stuffed with poems. To me, it looks so magical that I think I might see it lift him off the ground.

I hope we stay open to the unknown beauty that exists in our loved ones and our movie stars, offstage and beyond language, stigmas, diagnoses, and stereotypes. Amazing things can happen at any stage of life for famous people like Bruce Willis and for regular people like my dad, too, even in the wake of a seemingly terrifying diagnosis. Let’s celebrate that.